1 ) Phorusrhacids

Phorusrhacids would give even Alfred Hitchcock the shivers: Also known as terror birds , some were nearly 10 feet (3 meters) tall, weighed over half a ton (500 kilograms), and could swallow a dog in a single gulp. Their closest modern-day relatives are believed to be the 80 cm-tall seriemas.

Titanis walleri, one of the larger species, is known from Texas and Florida in North America. This makes the phorusrhacids the only known example of large South American predators migrating north during the Great American Interchange (which occurred after the volcanic Isthmus of Panama land bridge rose ca. 3 Ma ago).

It was once believed that T. walleri only became extinct around the time of the arrival of humans in North America.

2 ) Megalodon

Megalodon was an ancient shark that may have been 40 feet (12 m) long or even more. (There are a few scientists who estimate that it could have been up to 50 or 100 feet (15.5 or 31 m) long!) This is at least two or three times as long as the Great White Shark, but this is only an estimate made from many fossilized teeth and a few fossilized vertebrae that have been found.

These giant teeth are the size of a person’s hand! No other parts of this ancient shark have been found, so we can only guess what it looked like. Since Megalodon’s teeth are very similar to the teeth of the Great White Shark (but bigger and thicker), it is thought that Megalodon may have looked like a huge, streamlined version of the Great White Shark.

Megalodon’s diet probably consisted mostly of whales. Sharks eat about 2 percent of their body weight each day; this a bit less than a human being eats. Since most sharks are cold-blooded, they don’t have to eat as much as we eat (a lot of our food intake is used to keep our bodies warm).

3 ) Smilodon

Smilodon, often called Sabre-toothed cat is an extinct genus of machairodontine. The sabre-toothed cat was endemic to North America and South America, living from the Early Pleistocene through Lujanian stage of the Pleistocene epoch (2.5 mya—10,000 years ago).

Smilodon probably preyed on a wide variety of large game including bison, deer, American camels, horses and ground sloths. As it is known for the sabre-toothed cat Homotherium, Smilodon might have also killed juvenile mastodons and mammoths. Smilodon may also have attacked prehistoric humans, although this is not known for certain.

The La Brea tar pits in California trapped hundreds of Smilodon in the tar, possibly as they tried to feed on mammoths already trapped. The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County has many of their complete skeletons.

4 ) Estemmenosuchus

Estemmenosuchus (“Crowned Crocodile”) is a genus of large, early omnivorous therapsid that lived during the middle part of the Middle Permian period. It was among the largest animals of its day, and is characterized by distinctive horn-like structures, probably for intra-specific display.

Estemmenosuchus may have been warm-blooded either with an internal heat engine like mammals or what is called an inertial warm-bloodedness maintenance of a high body temperature by controlling loss of heat. This could be achieved by the build of this animal in that it was a large compact form with a low surface area to volume ratio-and so little heat escaped. At the moment scientists cannot resolve which theory is correct so they are content to work with two hypotheses testing them in the future to get closer to the truth.

5 ) Pterosaur

Pterosaurs were an order of flying reptiles that lived during the time of the dinosaurs. The pterosaurs ranged in size from a few inches to over 40 feet.

They had hollow bones, were lightly built, and had small bodies. They had large brains and good eyesight. Some pterosaurs had fur on their bodies, and some (like Pteranodon) had light-weight, bony crests on their heads that may have acted as a rudder when flying, or may have been a sexual characteristic.

Pterosaur wings were covered by a leathery membrane. This thin but tough membrane stretched between its body, the top of its legs and its elongated fourth fingers, forming the structure of the wing. Claws protruded from the other fingers.

QuetzalcoatlusPterosaurs could flap their wings and fly with power, but the largest ones (like Quetzalcoatlus, which had a wingspan up to 36 feet or 11 m wide) probably relied on updrafts (rising warm air) and breezes to help in flying.

6 ) Purussaurus

Purussaurus is an extinct genus of giant caiman that lived in South America during the Miocene epoch, 8 million years ago. It is known from skull material found in the Brazilian, Colombian and Peruvian Amazonia, and northern Venezuela.

Paleontologists estimate that P. brasiliensis may have measured around 11 to 13 metres (36 to 43 ft) in length, which means that Purussaurus is one of the largest crocodilians known to have ever existed.

Purussaur teeth are subcircular at their bases but somewhat flattened at the crown, and those of P. neivensis have been described as curving backwards and slightly inwards. These features all suggest that purassaurs were predators of vertebrates, perhaps grabbing large mammals, but also eating turtles, smaller crocodilians, fish and other prey.

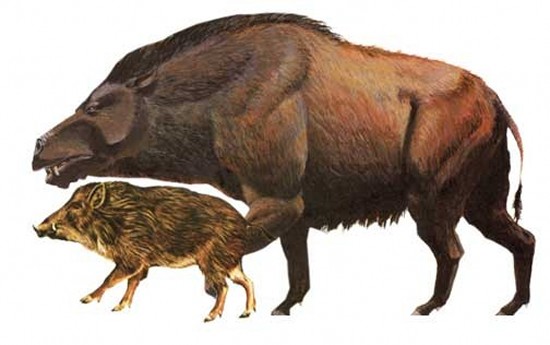

7 ) Daeodon

Daeodon (formerly Dinohyus), one of the largest, if not the largest, entelodont artiodactyls, lived 25-18 million years ago in North America. 3D reconstruction of Daeodon The 3.6 m (12 ft) long, 2.1 m (7 ft) tall (at-shoulder), 1 m long skull, 1000 kg mass animal strongly resembled a giant, monstrous pig or warthog, possessing huge jaws with prominent tusks and flaring cheekbones. It was a huge, bone-crushing scavenger and predator, found at Agate Springs Quarry.

The teeth were very distinctive: the incisors were blunt, while the canines were stout and must have been effective weapons. The neck was short and thick, and the spines in the anterior elements of the backbone were very long and formed a pronounced hump at the shoulders of the animal.

8 ) Gigantopithecus

Gigantopithecus is an extinct genus of ape that existed from roughly one million years to as recently as three-hundred thousand years ago, in what is now China, India, and Vietnam, placing Gigantopithecus in the same time frame and geographical location as several hominin species.

Gigantopithecus’s method of locomotion is uncertain, as no pelvic or leg bones have been found. The dominant view is that it walked on all fours like modern gorillas and chimpanzees; however, a minority opinion favor bipedal locomotion, most notably championed by the late Grover Krantz, but this assumption is based only on the very few jawbone remains found, all of which are U-shaped and widen towards the rear.

This allows room for the windpipe to be within the jaw, allowing the skull to sit squarely upon a fully-erect spine like modern humans, rather than roughly in front of it, like the other great apes.

The majority view is that the weight of such a large, heavy animal would put enormous strain on the creature’s legs, ankles and feet if it walked bipedally; while if it walked on all four limbs, like gorillas, its weight would be better distributed over each limb.